Witch Accusations and Persecution in Nepal

Structural violence under the aegis of tradition

by Nabin Baral

This webpage depicts instances of gender-based violence through images, text and audio. Parental guidance is necessary for viewers under the age of 18.

In different parts of the world, witch accusations and persecutions continue to represent a serious form of gender-based violence, even in the 21st century. In Nepal, where centuries-old superstitious beliefs are deep-rooted in the social and cultural structures of society, beliefs in witchcraft often lead to physical and psychological violence, with most victims being poor, single or marginalised women living in rural environments and, particularly, Dalit.

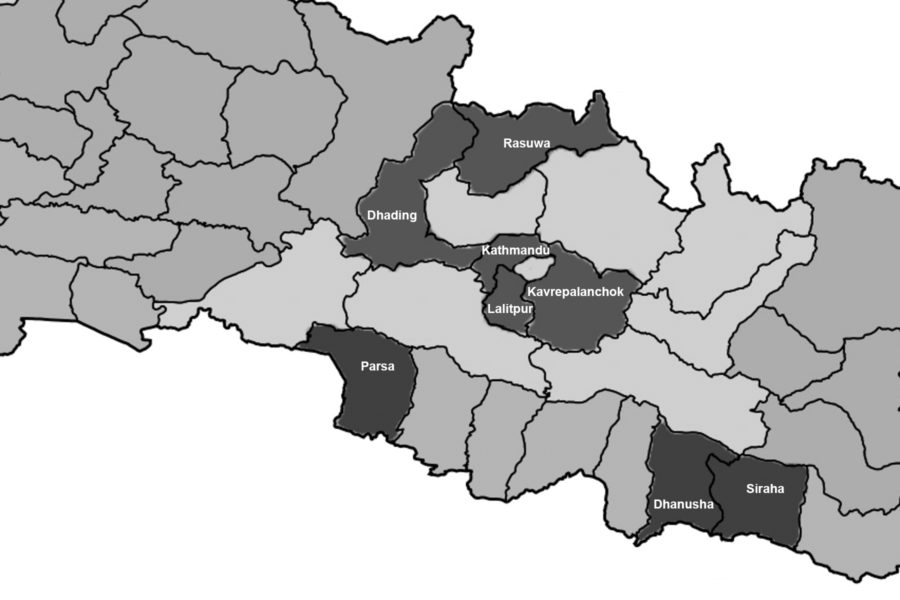

One example of superstition’s prevalence is the Ghost Festival, which takes place annually on the banks of the Kamala River, in the Dhanusha and Siraha districts of Nepal. Thousands of pilgrims visit with their dhamis (shamans), who claim to have the power to eradicate misfortunes such as failing crops, illness, or family difficulties. Here superstitious beliefs correlate with structural injustices, including gender discrimination, access—to health services, education, economic opportunities and legal advice—as well as corruption.

This photo essay documents the dire need for awareness to be raised at both grassroots and national levels, and, following this, for change. This body of work is not against any religion, culture or ethnic groups in Nepal.

One example of superstition’s prevalence is the Ghost Festival, which takes place annually on the banks of the Kamala River, in the Dhanusha and Siraha districts of Nepal. Thousands of pilgrims visit with their dhamis (shamans), who claim to have the power to eradicate misfortunes such as failing crops, illness, or family difficulties. Here superstitious beliefs correlate with structural injustices, including gender discrimination, access—to health services, education, economic opportunities and legal advice—as well as corruption.

This photo essay documents the dire need for awareness to be raised at both grassroots and national levels, and, following this, for change. This body of work is not against any religion, culture or ethnic groups in Nepal.

Genesis of the project

During my childhood, I witnessed the superstitious and violent treatment of a witch-doctor upon my mother, who was suffering from a mental health condition. Later on, while a student in Kathmandu, I used to read news of Witchcraft Accusations and Persecution (WAP) in national dailies time and again. I was really shocked by the news of WAP in February 2012. Thageni Mahato, a 40 year-old woman, had been burnt to death by villagers led by dhamis (shamans) in the Chitwan district of Nepal.

The following year, I read the news of Parbati Devi Chaudhary’s death by beating, perpetrated by a group of neighbours in the remote village of Supauli, in the Parsa district of Nepal. That night, Parbati and three other women were identified as witches by a dhami brought into the village by a neighbour. Two of the women fled the village, and the third one, Rajpati Devi Chaudhary, was still living in isolation and terror at the time of my visit.

I decided to document the event and its aftermath in the form of a photo story and went to Supauli a week after the incident. I took help from security forces as there was a threat from the villagers and neighbours who were involved in the murder.

The following year, I read the news of Parbati Devi Chaudhary’s death by beating, perpetrated by a group of neighbours in the remote village of Supauli, in the Parsa district of Nepal. That night, Parbati and three other women were identified as witches by a dhami brought into the village by a neighbour. Two of the women fled the village, and the third one, Rajpati Devi Chaudhary, was still living in isolation and terror at the time of my visit.

I decided to document the event and its aftermath in the form of a photo story and went to Supauli a week after the incident. I took help from security forces as there was a threat from the villagers and neighbours who were involved in the murder.

read more

Sunkesi Chaudhary shows a photo of her mother, Parvati Devi Chaudhary, who was beaten to death at midnight on 16 August 2013. She was 45 years old. 24 August 2013, Supauli, Parsa, Nepal.

Sunkesi Chaudhary, Parsa, 2013

read more

Bhagan Chaudhary, the husband of the late Parvati Devi, stands near their bed, out of which she was forcefully dragged. 24 August 2013, Supauli, Parsa, Nepal.

read more

Rajpati Devi Chaudhary, 55, was also accused of being a witch on the day of Parvati Devi Chaudhary’s murder. Rajpati recounts the events and how she fears for her life. 24 August 2013, Supauli, Parsa, Nepal.

read more

Bhagan Chaudhary walks towards the crossroad where his wife was killed. 24 August 2013, Supauli, Parsa, Nepal.

read more

According to a traditional ritual, Bhagan Chaudhary holds the soul of his wife with him for 13 days in an iron nail embedded in a bamboo stick. 24 August 2013, Supauli, Parsa, Nepal.

read more

Bhagan Chaudhary chases away dogs who try to eat the food offered to his wife’s soul. 24 August 2013, Supauli, Parsa,

Nepal.

Branded as witches

After visiting the Chaudhary family, I continued documenting the stories and experiences of women being branded as witches.

On 10 December 2013, the last day of the 16-day global campaign against violence against women, Chanamati Magrati was beaten to unconsciousness by her neighbours in a remote village of the Dhading district. Chanamati, who is from a modest farmer community, was living with her two children in the village, while her husband was working as a labourer in Kathmandu to sustain his family.

After the incident, Chanamati said, “They attempted to kill me with a sickle, but I managed to save my neck”. Pampha Magriti, a 30 year-old Dalit woman, was also beaten unconscious in her attempt to save Chanamati Magrati. “The physical wounds in my body may recover as time goes, but the pain in my heart will never recover. They accused me of being a witch”, Chanamati added with great grief.

Kulpi B. K. and Kalli Kumari B. K., the two other victims of witch accusations portrayed in this story, are, like Chanamati Magrati, Dalit and therefore socially and economically vulnerable.

On 10 December 2013, the last day of the 16-day global campaign against violence against women, Chanamati Magrati was beaten to unconsciousness by her neighbours in a remote village of the Dhading district. Chanamati, who is from a modest farmer community, was living with her two children in the village, while her husband was working as a labourer in Kathmandu to sustain his family.

After the incident, Chanamati said, “They attempted to kill me with a sickle, but I managed to save my neck”. Pampha Magriti, a 30 year-old Dalit woman, was also beaten unconscious in her attempt to save Chanamati Magrati. “The physical wounds in my body may recover as time goes, but the pain in my heart will never recover. They accused me of being a witch”, Chanamati added with great grief.

Kulpi B. K. and Kalli Kumari B. K., the two other victims of witch accusations portrayed in this story, are, like Chanamati Magrati, Dalit and therefore socially and economically vulnerable.

read more

Chanamati Magrati, a week after having been beaten unconscious by her neighbours. 17 December 2013, Dhading, Nepal.

read more

Chanamati Maggrati and her son call their pig in the evening as they are afraid to go towards the other houses in

the village. 17 December 2013, Dhading, Nepal.

read more

Chanamati Maggrati is being treated at her nearest health post, a 5-hour walk through the mountains. 18 December 2013, Dhading, Nepal.

read more

Chanamati Maggrati’s trouser stained with blood. 18 December 2013, Dhading, Nepal.

read more

Chanamati Magrati’s husband helps her cook while she is injured. He works in Kathmandu as a labourer and came home after hearing his wife had been beaten by their neighbours. 17 December 2013, Dhading, Nepal.

read more

Pampha Magriti, 30, a Dalit woman, was severely beaten when she tried to help Chanamati Maggrati during the attack. 17 December 2013, Dhading, Nepal.

read more

Kulpi B. K., 55, a Dalit woman at her house in the village of Ningalapani. Kalpi was beaten by neighbours and left for dead in

2010. “As I live alone, I face

discrimination every day from some of the villagers”. 19 December 2013, Dhading, Nepal.

read more

On 20 March 2009, Kalli Kumari B. K., a 50 year-old Dalit woman, was accused of practicing witchcraft by a group of villagers led by the local school’s headmistress. She was beaten and forced to eat her own excreta in public. “I accepted that I am witch when they took blades out to chop my breasts. I had no other choice at that time”. 2 January 2014, Lalitpur, Nepal.

Kalli Kumari B.K, Lalitpur, 2014

read more

A dhami humiliates Kanti Yadav, 103, as he accuses her of being a witch. 5 November 2014, Dhanusha, Nepal.

Ghost Festival

Each year, hundreds of thousands of people visit the Kamala River on the eve of the full moon of Kartik, the seventh month of the Nepali calendar.

They come with dhamis with the hope that they will help them eradicate their illness, which they believe is caused by either the family god Kula-dèvatā, a ghost, or an evil person in their surroundings. A series of rituals involving worship, exorcism, trance, and purification take place in the lead up to the full moon. The devotion of thousands of people toward the dhamis renews centuries-old superstitious beliefs and maintains the superior position of dhamis, who frequently engage with violence.

I heard about the festival in 2011 and first visited in 2014. I have returned three times since.

They come with dhamis with the hope that they will help them eradicate their illness, which they believe is caused by either the family god Kula-dèvatā, a ghost, or an evil person in their surroundings. A series of rituals involving worship, exorcism, trance, and purification take place in the lead up to the full moon. The devotion of thousands of people toward the dhamis renews centuries-old superstitious beliefs and maintains the superior position of dhamis, who frequently engage with violence.

I heard about the festival in 2011 and first visited in 2014. I have returned three times since.

read more

Thousands of people visit the Kamala River on full moon day to eradicate evil spirits or problems created by the family god Kula-dèvatā. 6 November 2014, Dhanusha, Nepal.

read more

Rinku Yadav, 20, is believed to be possessed by an evil spirit. She is healed by dhami Paltan Mukhiya. 4 November 2017, Dhanusha, Nepal.

read more

Women in trance on the eve of the Kartik full moon. 3 November 2017, Dhanusha, Nepal.

read more

Women in trance on the morning of the Kartik full moon, in the Kamala River. 6 November 2014, Dhanusha, Nepal.

read more

A woman is made to immerse herself into the Kamala River by a dhami, on the morning of the Kartik full moon. 6 November 2014, Dhanusha, Nepal.

read more

Two dhamis use force to purify a woman believed to be possessed by an evil spirit. 4 November 2017, Dhanusha, Nepal.

Twenty-seven ghosts and witches

Back in 2019, Urmila Yadav, from the Dhanusha district, believed that she was possessed. The dhamis she consulted in her district identified that she was possessed by twenty-seven ghosts and witches. Urmila and her family believed that those ghosts and witches were the cause of the family’s financial problems, deaths and poor relations between members. At the Ghost Festival, Urmila faced violent exorcism at the hands of dhamis.

As a documentary photographer, to see violence in front of you is really difficult. In these situations, I am a witness with a camera and I must conceal my aim of capturing violence. I tell my subjects that I am here to document their culture, which gives me a licence to observe them. If I witness a situation that is life-threatening, I react and act. I see in my photographs the potential to challenge structural violence.

As a documentary photographer, to see violence in front of you is really difficult. In these situations, I am a witness with a camera and I must conceal my aim of capturing violence. I tell my subjects that I am here to document their culture, which gives me a licence to observe them. If I witness a situation that is life-threatening, I react and act. I see in my photographs the potential to challenge structural violence.

read more

Urmila Yadav, 24, (third from last), circles around a temple near her house, a day before heading to the Kamala River for the Ghost

Festival. 10 November 2019, Dhanusha, Nepal.

read more

Later that day, a young dhami uses force during an interrogation to make Urmila Yadav reveal the names of the ghosts and witches that possess

her. 10 November 2019, Dhanusha, Nepal.

read more

The evening of rituals continue until the early hours of the morning. An elderly dhami resorts to domination to exorcise Urmila Yadav. 11 November 2019, Dhanusha, Nepal.

read more

Urmila Yadav travels to the Ghost Festival on a tractor with dhamis and other villagers. She carries a protective stick given to her by a dhami. On the right, a woman also believed to be possessed hugs a female dhami. 11 November 2019, Dhanusha, Nepal.

read more

On the day of the Kartik full moon, Urmila Yadav and another pilgrim get into a trance in the Kamala River. 12 November 2019, Dhanusha, Nepal.

read more

Urmila Yadav with her protective stick after taking a bath in the Kamala River. Dhamis claim that after this ritual she will be freed

from ghosts and witches. 12 November 2019, Dhanusha, Nepal.

read more

Eighteen months later, I visited Urmila Yadav. She told me she had been rid of the twenty-seven ghosts and witches, but I could not see happiness on her face. Urmila went back to the Ghost Festival in 2020, and will visit it for three more consecutive years. 13 March 2021, Dhanusha, Nepal.

Shamans

Shamanism is integral to cultural and religious practices in Nepal. Mostly on the occasion of the August and November full moons, shamans gather in festivals in different locations across Nepal to practice their rituals. Janai Purnima and Kartik Purnima are two such festivals. During Janai Purnima, thousands of Hindu and Buddhist pilgrims flock to Gosaikunda Lake in their quest for holy water.

Shamans called jhakaris or dhamis are traditional healers who are believed to cure sickness caused by evil spirits, thanks to their ability to communicate with spirits and gods. They practice exorcism and chant magical incantations, and in some cases use traditional herbs and medicinal techniques to cure those who visit them. Some shamans even refer to doctors if they see that the sickness needs modern medical treatment.

However, many shamans also resort to violent exorcism and are responsible for identifying someone as a witch—in particular in Nepali villages with limited access to modern healthcare facilities—which leads to hurt, trauma or loss of life. While the cultural elements of shamanic practice are precious, more urgent still is the need to raise awareness of unethical practices among shamans in order to eradicate violence and witch accusations and persecution.

Shamans called jhakaris or dhamis are traditional healers who are believed to cure sickness caused by evil spirits, thanks to their ability to communicate with spirits and gods. They practice exorcism and chant magical incantations, and in some cases use traditional herbs and medicinal techniques to cure those who visit them. Some shamans even refer to doctors if they see that the sickness needs modern medical treatment.

However, many shamans also resort to violent exorcism and are responsible for identifying someone as a witch—in particular in Nepali villages with limited access to modern healthcare facilities—which leads to hurt, trauma or loss of life. While the cultural elements of shamanic practice are precious, more urgent still is the need to raise awareness of unethical practices among shamans in order to eradicate violence and witch accusations and persecution.

read more

On August’s full moon day, during Janai Purnima, a dhami treks back home through Langtang National Park after taking a holy bath in Gosaikunda Lake. 26 August 2018, Rasuwa, Nepal.

read more

Children watch dhamis perform during Janai Purmina on the eve of the August full moon. 28 August 2015, Timaal, Kavrepalanchok, Nepal.

read more

People, and especially women, sit inside a circle formed by dhamis to treat their illness and

other life problems believed to be created by evil sprits. 29

August 2015, Kavrepalanchok, Nepal.

read more

A woman dhami performs during the treatment of a patient. 9 December 2014, Kathmandu, Nepal.

read more

Dhami Chet Bahadur Tamam uses the photo of the patient’s husband to distance-treat him for infidelity. 9 December 2014, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Chikana

Since 2020, I have taken my documentary research to the village of Chikana, in the Siraha district of Nepal. Mostly constituted of Dalit households, Chikana is located on the bank of the Kamala River, where the annual Ghost Festival takes place.

In Chikana I am looking for meaningful visuals that testify to the specific socioeconomic and political landscape of the place, and the underlying discrimination and corruption. Education, health, gender relations and land poverty are some of the issues which, I believe, directly or indirectly lead to cases of witchcraft accusations and persecution.

Unlike my previous photo works, this series does not represent violence; instead, it observes the conditions that facilitate that very violence. This new phase of my work is still in progress at the time of writing, in spring 2021.

In Chikana I am looking for meaningful visuals that testify to the specific socioeconomic and political landscape of the place, and the underlying discrimination and corruption. Education, health, gender relations and land poverty are some of the issues which, I believe, directly or indirectly lead to cases of witchcraft accusations and persecution.

Unlike my previous photo works, this series does not represent violence; instead, it observes the conditions that facilitate that very violence. This new phase of my work is still in progress at the time of writing, in spring 2021.

read more

Young girls return home after cleaning utensils in the Kamala River. 19 Feburary 2020, Chikana, Siraha, Nepal.

read more

Young boys hang around near the river bank. 29 November 2020, Chikana, Siraha, Nepal.

read more

Chandani Kumari Mukhi, who studies in class three, helps her parents with river bed cultivation. 13 March 2021, Chikana, Siraha, Nepal.

read more

Landless farmers from Chikana use small sticks around cucumber plants to save them from being blown away. The people in Chikana cultivate in the sandy bed of the Kamala River during the dry season. 13 March 2021, Siraha, Nepal.

read more

A landless woman from Chikana separates the grain from the husks on the bank of the Kamala River. 29 November 2020, Chikana, Siraha, Nepal.

read more

People from Chikana bathe their buffalo in the Kamala River. 19 February 2020, Siraha, Nepal.

Resources

Reports:

“Literature Review on Harmful Practices in Nepal“, UNFPA Nepal, 2020

“Witchcraft Accusations & Persecution in Nepal“, Witchcraft and Human Rights Information Network (WHRIN), 2014

Conversations:

“Branded as Witches: A Conversation across Geographies and Times—Nabin Baral with Anna Colin“, WOW Week 2021, 5 March 2021

“Witch Accusation and Persecution: Marani Devi in conversation with Pallavi Payal“, WOW Virtual Nepal 2020, 22 October 2020

“Witch Accusation and Persecution: Nabin Baral in conversation with Anjana Luitel“, WOW Virtual Nepal 2020, 2 September 2020

Compiled by Nabin Baral:

“Complexities of injustice“, The Kathmandu Post, 30 November 2019

“Witch Accusation and Persecution“, short documentary, British Council Nepal, August 2020

Relative to Nabin Baral’s work on the subject:

“Celebrating indigenous women narratives“, by Srizu Bajracharya, The Kathmandu Post, 4 December 2019

“Literature Review on Harmful Practices in Nepal“, UNFPA Nepal, 2020

“Witchcraft Accusations & Persecution in Nepal“, Witchcraft and Human Rights Information Network (WHRIN), 2014

Conversations:

“Branded as Witches: A Conversation across Geographies and Times—Nabin Baral with Anna Colin“, WOW Week 2021, 5 March 2021

“Witch Accusation and Persecution: Marani Devi in conversation with Pallavi Payal“, WOW Virtual Nepal 2020, 22 October 2020

“Witch Accusation and Persecution: Nabin Baral in conversation with Anjana Luitel“, WOW Virtual Nepal 2020, 2 September 2020

Compiled by Nabin Baral:

“Complexities of injustice“, The Kathmandu Post, 30 November 2019

“Witch Accusation and Persecution“, short documentary, British Council Nepal, August 2020

Relative to Nabin Baral’s work on the subject:

“Celebrating indigenous women narratives“, by Srizu Bajracharya, The Kathmandu Post, 4 December 2019

Credits

All photos are by Nabin Baral, documentary photographer based in Kathmandu, Nepal.

This webpage was compiled and edited by Nabin Baral, together with independent curator Anna Colin, UK. It was developed and designed by Ravindra Adhikari.

This web presentation was made possible thanks to the British Council.

This webpage was compiled and edited by Nabin Baral, together with independent curator Anna Colin, UK. It was developed and designed by Ravindra Adhikari.

This web presentation was made possible thanks to the British Council.